I have been obsessed with this. The emotions it brings up are confusing and compelling and I still don’t quite know what it’s communicating. It’s mood is just at the edge of recognition. So, I’m doing closer listenings than before and hope to understand it better.

Below are videos of the specific obsessions: Ferneyhough’s Lemma Icon Epigram (1981): Brian Ferneyhough – Lemma Icon Epigram w/ score (YouTube)

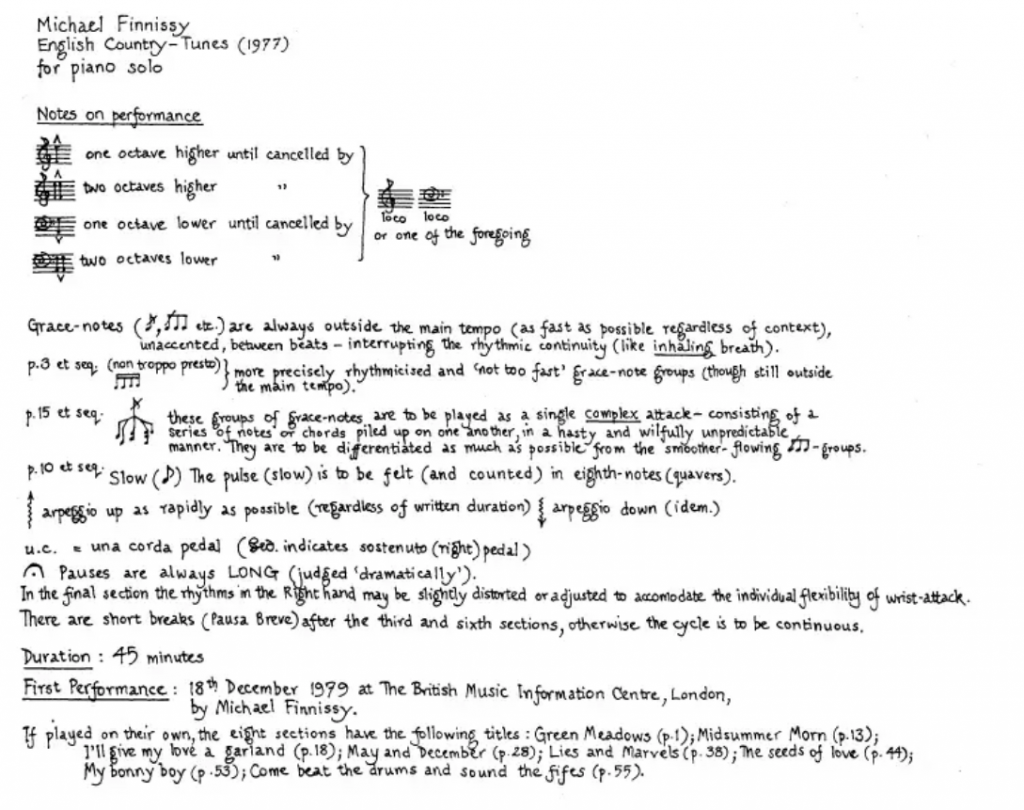

Finnissy’s English Country Tunes (1977). The complete work, I believe performed by the composer: Finnissy – English Country Tunes [Audio + Score] (YouTube).

- Unsettled (violent and reckless), “Green Meadows” (0:03) (page 1)

- Slow and wistful, “Midsummer Morn” (10:59) (page 13)

- Tranquil, “I’ll give my Love a Garland” (16:26) (page 18)

- Gently (no accel.), “May and December” (26:38) (page 28)

- Forceful and boisterous (but not too hurried), “Lies and Marvels” (33:29) (page 38)

- Very rapid and energetic, “The Seeds of Love” (37:40) (page 44)

- Slowly, simply, and peacefully, “My Bonny Boy” (41:42) (page 53)

- Presto, “Come beat the Drums and Sound the Fifes” (48:39) (page 55)

(Been listening to very much this, esp. “I’ll give my Love a Garland” which is particularly expressive.)

I’ve ordered the scores for both from Sheet Music Plus (Lemma-Icon-Epigram and English Country-Tunes). I’m not sure if that’s the best site to order sheet music (is there a best?) but it’s where I started ordering years ago and so you stick with your habits. Because they’re habits. I avoid Amazon for vinyl and only shop at Discogs both to avoid the Amazon tar pit and because Discogs is a great site for searchin’ rare-ish albums. Much just can’t be found locally (the Cambodian music I found at the local Wax N Facts and the Vietnamese music from the same label from Discogs being a cross-pollinating exception). Similarly, I would never get sheet music from Amazon if I could help it. I did check the composers’ web sites for direct purchase: Ferneyhough has no web site but his music is available at Editions Peters; Finnissy does have a web site, and sells scores through a site called Composers Edition, but English Country-Tunes is not there.

A certain shame nags at me when I order piano music I cannot play. It’s stupid, but it feels like putting Impressive Books on your shelf that you’ll never read in the hope that it will impress the guests. It’s why the word “gauche” was invented. Yeah, it is stupid.

(I recently bought a study score of the Brandenburg Concertos and I can’t play them. So what’s the problem?!)

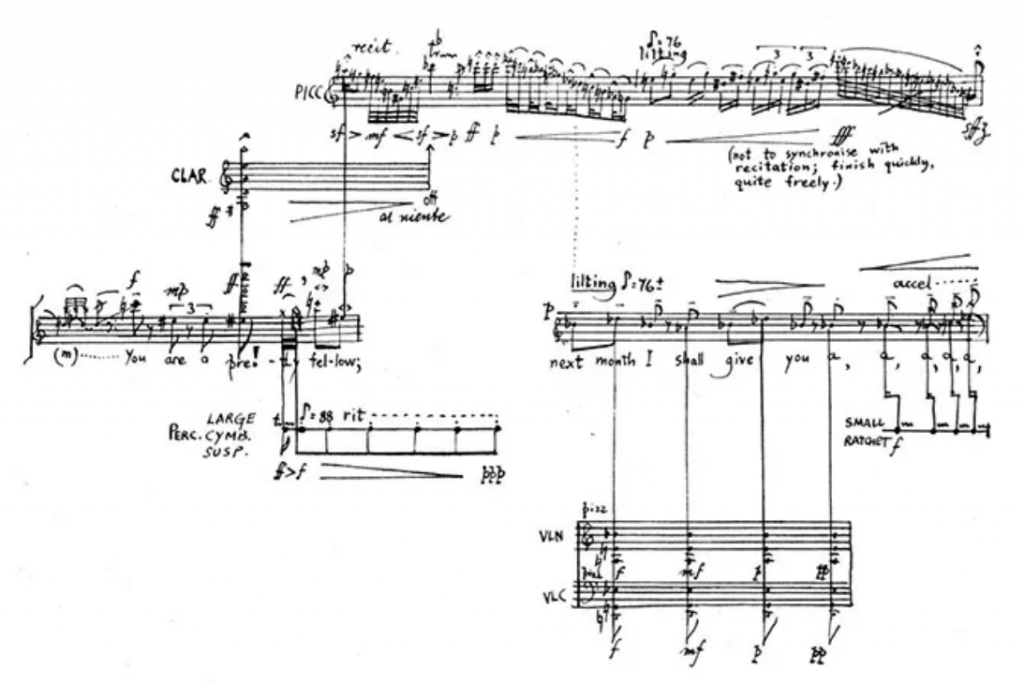

And the scores are just beautiful. The requirements to notate modern music stretches the limits of what western music notation, at least as typesetting, accommodates. I had mentioned before (when I was reading about Die Teufel von Loudun by Penderecki) what a striking score Peter Maxwell Davies created for Eight Songs for a Mad King (above image). Modern avant-garde has many examples. I forget where, years ago, we saw Cage scores as part of a museum exhibition and they were shocking and just absolutely surprising in what they accomplished in communicating the “fullness” of his work across odd mediums using graphic notation. Similarly but differently, Finnissy’s is note-based, but with creative additions. His single-stem grace notes are a more striking example, and one that enhances notation in a way that communicates the intent.

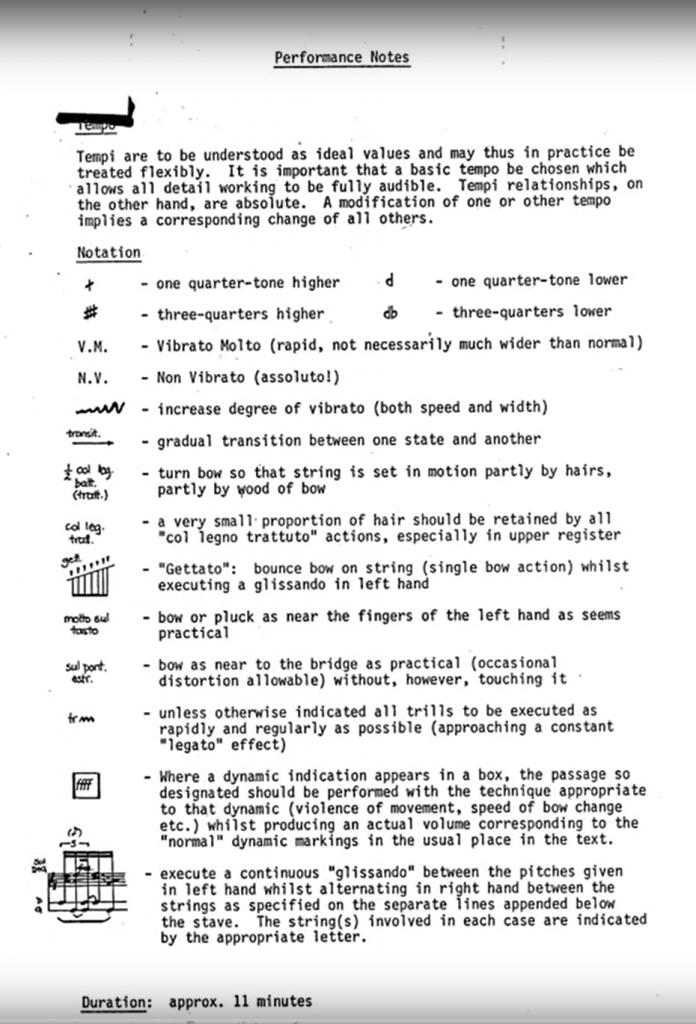

The performance notes from Ferneyhough’s String Quartet No. 2 present and even further extension of creative notation.

There’s a certain shame, also, that nags me when I think that part of my love of the music is because of these stunning scores. I’m responding to visual along with auditory interest, but as a musician I don’t want to feel that the former is the primary.

References:

- A guide to contemporary classical music (The Guardian) – A resource for ~40 or so 20th and 21st century composers. Accessible.

- A guide to Brian Ferneyhough’s music (10 Sep 2012) Referenced in my previous post.

- A guide to Michael Finnissy’s music (23 Jul 2012)

- Finnissy English Country-Tunes – A review on Gramophone of a 1986 recording of Finnissy performing his work.

Michael Finnissy’s music is intricate in texture, but strongly built on the basis of clearly perceptible and well-proportioned contrasts between the aggressive and the restrained…

Beneath its modernist surface Finnissy’s piano writing has a Lisztian range, alternating bell-like meditations with virtuosic outbursts: as it happens, he studied with, among others, the Liszt expert Humphrey Searle…

Finnissy is an ideal advocate of his own music, making it plain that its technical demands are not ends in themselves but the only means whereby so powerful an expressive display can convincingly be mounted.

from the Gramaphone review