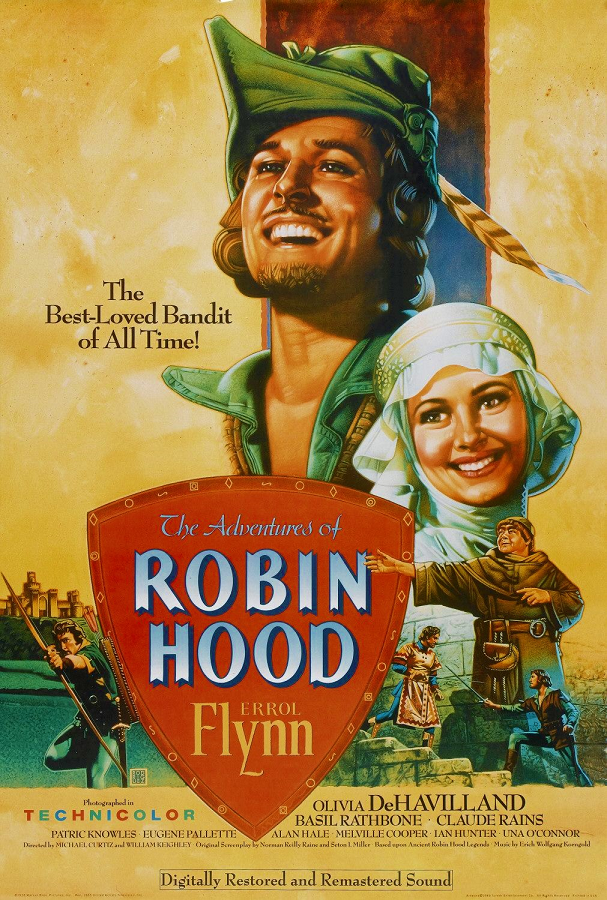

I don’t know when I first watched this, but somehow it imprinted on me and every X years I must re-watch and re-live the absolute joy of seeing the Merry Men drop from trees in absurd synchronization, Errol Flynn look with furtive slyness as King Richard’s despot brother’s archers advance on him, and Marian (I can never remember it’s with an “A”) play the haughty-then-human royal ward. And the movie’s Technicolor goodness is a perfect presentation of the mood. That and Korngold’s soundtrack make it an absolute classic.

Moving on from my 60s/70s Italian and Iron Curtain sci-fi obsessions but continuing my Japanese pink film and peplum obsession, I’m now obsessed with Robin Hood and man is there a lot of research to dive into. I’ll also start watching the many good (but mostly bad) tellings of Robin Hood in the cinematic cannon.

The Adventures of Robin Hood references:

- The Adventures of Robin Hood at IMDB

- The Adventures of Robin Hood at Wikipedia

Some general Robin Hood references:

- Robin Hood page at Wikipedia

- Robin Hood category at Wikipedia

- Robin Hood characters category at Wikipedia

- International Robin Hood Bibliography

- The Real Robin Hood at History.com (of only moderate value)

The first known historical references to a Robin Hood come from around the 1200s. Even prior, across Europe, there are records of individuals named Robin/Robyn/Robert Hood/Hude/Hode (the surname being someone who either makes or wears hoods, natch) but none tied to the history or legend. By the 1200s in England, there are references to Robinhood/Robehod/Robbehod as an actual thief or whatnot.

This gets us to the legend as it appears in literary artifacts. Wikipedia is kind of a mess of references, but I’m going to start going through some of the key ones.

- Piers Plowman (~1367-1380s)

- Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland (1420)

- A Gest of Robyn Hode (1492-1534)

One often-cited is from ~1367-1380s in an extended narrative poem titled Piers Plowman by William Langland (1330?-1400?). The poem exists in three forms (A- B- and C-texts) pieced together from 50-56 distinct manuscripts, some complete and some just fragments. It is held in high regard as one of the great works of English literature in the Middle Ages (cf. Canterbury Tales from ~20 years later in 1387-1400). The three different versions contain fundamental differences consisting of additions/deletions/alterations, with the A-text from ~1367-1370 spanning 2,500 lines yet unfinished, the B-text from ~1377-1379 altering and extending A to 7,300 lines, and the C-text from the 1380s altering all but the final sections of the B-text. With all of the manuscripts existing in various forms, scholarly analysis both historical and literary is, as you can imagine, extensive.

The (tiny) quote from Piers Plowman (in its entirety) is:

I kan noȝt parfitly my Paternoster as þe preest it syngeþ,

Passus V, lines 216-217 (A-text) or 394-395 (B-text), transcribed at International Robin Hood Bibliography

But I kan rymes of Robyn hood and Randolf Erl of Chestre.

Ich can nouht parfytliche my pater-noster as the priest hit syngeth

Passus VIII, lines 11-12, copied from the image below

Ich can rymes of Robin Hode , and of Randolf erl of Chestre

I know not Paternoster · as the priest it singeth, But I know rhymes of Robin Hood · and Earl Randolph of Chester

translation from The Geoffrey Chaucer Page

Piers Plowman references:

- Piers Plowman at Wikipedia

- Piers Plowman B-text at The Piers Plowman Electronic Archive

- Piers Plowman (likely B-text) at the Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse

The Piers Plowman quote is short and, let’s face it, pretty bereft of any Merry Men or Sheriffs or Maids. A more substantive allusion, though nearly as short, is contain in Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland (1420) compiled by Andrew of Wyntoun (~1350-~1425). It is written couplets spanning 30,000 verses and contained in nine books divided into chapters. Wyntoun wrote and compiled it as a history of Scotland from the creation of the Earth (!) up to 1420.

The quote appears under a dated entry going back to 1283 (also: bonus Little John reference!).

Lytil Jhon and Robyne Hude

Orygynale Chronicle, from Wikipedia

Wayth-men ware commendyd gude

In Yngil-wode and Barnysdale

Thai oysyd all this tyme thare trawale.

I couldn’t find any “official” modern English translation online but found a discussion thread with several skilled attempts. Here’s one of the more lyric translations:

In Barnsdale and Inglewood,

from a thread at The Free Dictionary Language Forums

Where they plied their robbers trade

Little John and Robin Hood

Good reputations made.

Inglewood is Inglewood Forest. Barnsdale is a site in the Parish of South Kirkby.

Orygynale Cronykil references:

- Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland at Wikipedia

- The orygynale cronykil of Scotland. By Andrew of Wyntoun. Edited by David Laing scan of the book from The Internet Archive

A Gest of Robyn Hode is documented in the Child Ballads anthology created by Francis James Child (1825-1896), which was subsumed by the Roud Fold Song Index by Steve Roud (1949-). The Roud index is a database of ~25,000 English-language folk songs organizing previous anthologies and expanded with Roud’s index of field recordings. A Gest of Robyn Hode is Child 117 from Volume 3 Part 5, and Roud No. 70. The source text from the Child Ballads consists of 456 four-line verses. Scholars believe it was written in the 1400s though it’s narrative (based on contemporary references within the text) is the 1330s or 1340s.

Familiar characters from the song include Little John, Much, Will Scarlet, and an un-named sheriff. There is also the iconic scene of the archery contest.

Lythe and listin, gentilmen

the first stanza, taken from The English and Scottish popular ballads

That be of frebore blode;

I shall you tel of gode yeman

His name was Robyn Hode.

A Gest of Robyn Hode references:

- A Gest of Robyn Hode at Wikipedia

- Child Ballads

- Roud Fold Song Index

- The English and Scottish popular ballads (aka the Child Ballads) scan of the book from The Internet Archive. The historic and linguistic analysis of A Gest of Robyn Hode starts at page 38 with the actual ballad running from page 56 to 78.

Much more to research.