Different from when I finished the symphony, near the end of finishing the string quartet I immediately had an idea for this next work. The in-between-time in this instance is not downtime, but rather a period spent on research.

For (manymany) years I’d had the idea but never had the resources–or perhaps commitment–to approach it. The concept was a natural result of a classical/modernist listener who early on listened to Qbert, Invisibl Skratch Piklz, Shadow, et al. Choosing a sonata-like approach was an equally natural result for something that lends itself best as a solo instrument.

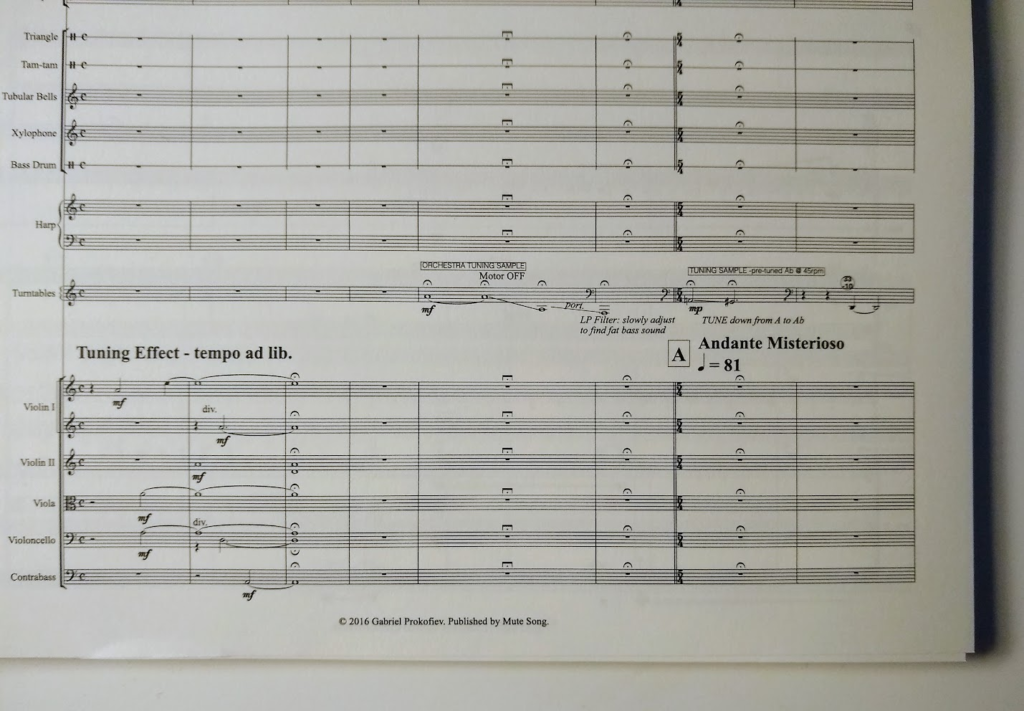

The only examples of a classical approach to composing for turntables I can find are from Gabriel Prokofiev, who has written several works for turntables and orchestra. There may be more, but searching for combinations of “turntable”, “scratch”, “orchestra”, “classical”, etc. predictably turns up only false positives. Of those Prokofiev works, only one is recorded–his first concerto–and only the others have study scores available. I purchased the study score for his Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra No. 2 to see how he integrates it into an ensemble setting.

He uses standard Western music notation, possibly for convenience, with annotations for various effects along with pitch designation. The pitch is likely mapped to the samples that are used which, if they are done in a similar manner as with his Concerto No. 1, are made up at least partly of recordings of the orchestra itself. From his programme notes:

What seemed the most natural solution was that the DJ should scratch and play with sounds that were generated by the chamber orchestra themselves so that no foreign sounds would ever enter the piece. For the necessary gasping sounds I could record the woodwind players and for the drum sounds record the orchestral percussion section playing passages from the concerto itself. Instead of the test-tone we would sample a flute note for the melodic section.

Programme notes for Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra No.1 (2006)

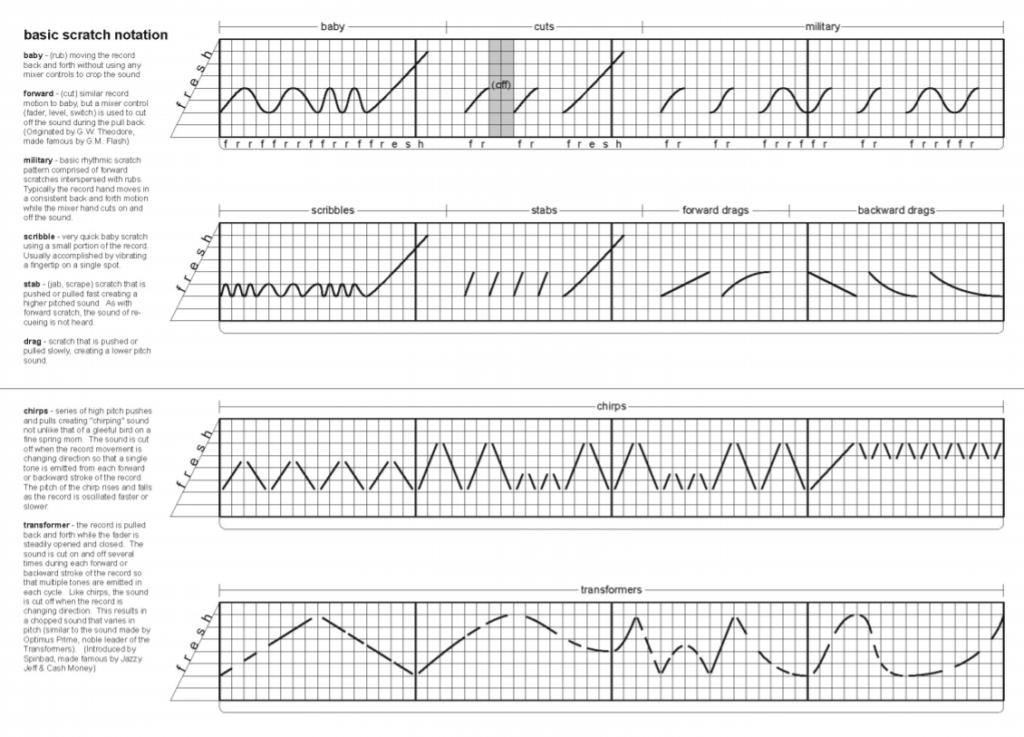

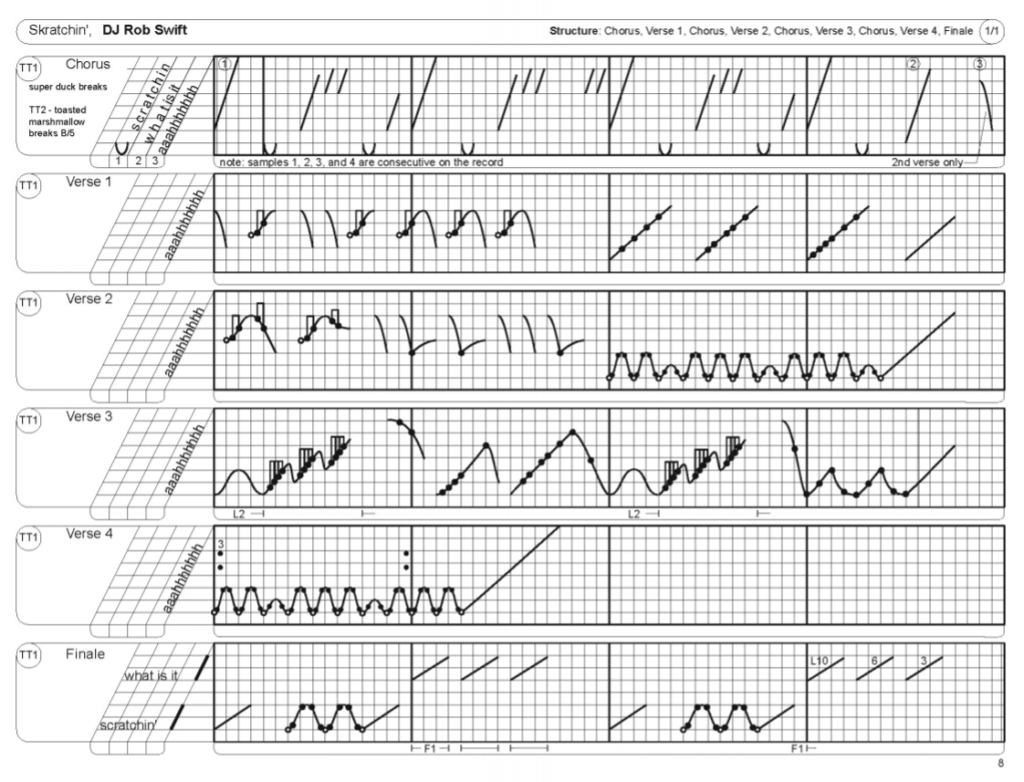

The somewhat inexpressiveness of standard notation is answered with two attempts at codifying turntablism using a new notation. One is a more graphical representation (Turntablist Transcription Methodology (TTM), pdf here, created by John Carluccio); the other is based on standard notation with a considerable number of embellishments (S-Notation (pdf), created by Alexander Sonnenfeld). Both have their advantages and drawbacks. To get a sense of the range of sounds that a notation system must be capable of transcribing, there’s a good list at Timothy Wisdom’s website with the standard scratch techniques.

TTM notation is immediately readable with just a few nuances that may need explaining to fully “hear” the intent of a score.

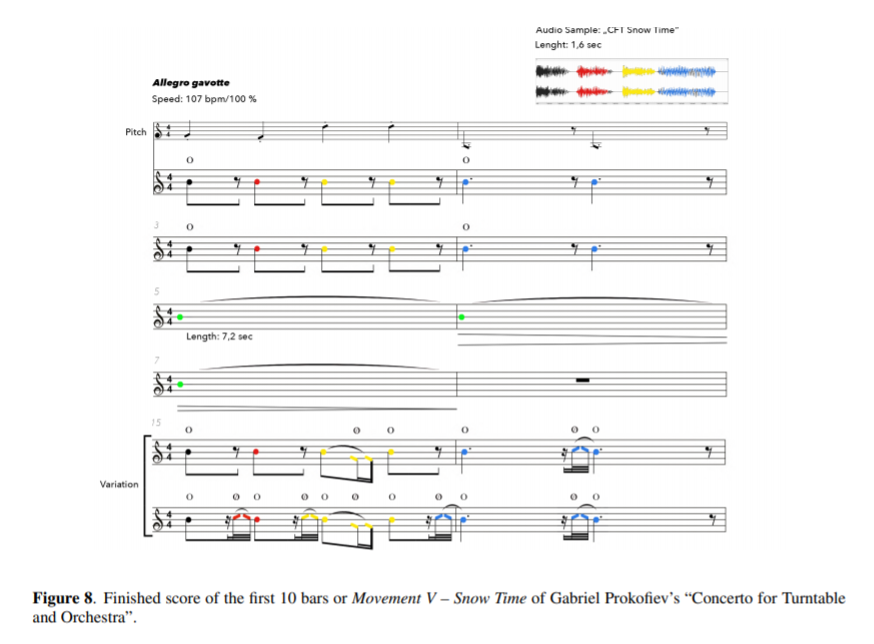

S-Notation, though it piggybacks on standard notation, is surprisingly more difficult, but also–likely causing that difficulty–has the potential for more expressive communication.

S-Notation captured a more exact sense of rhythm than TTM (somewhat ironically), but its use of colors to denote sections of the waveform plot that make up the sample makes it more difficult to compose with. Who has colored pencils lying around? The “S” clef is a really nice touch though!

I’ve adopted my own method in a manner similar to the way that Gabriel Prokofiev has walked a middle ground between standard and S-Notation.

Since I compose in Dorico now, I first needed a VST audio plugin capable of producing sounds or, if there were none available, one that I could use to create a library of scratch effects from existing samples. After my failed searches, my brother-in-law found a plugin called UVI Scratch Machine. It comes with a library of dozens of samples, along with hundreds of variations for each sample. For example, it has 259 variations of just the classic “Fresh” sample, and each can be altered with a host of effects (see the interface below). Perfect.

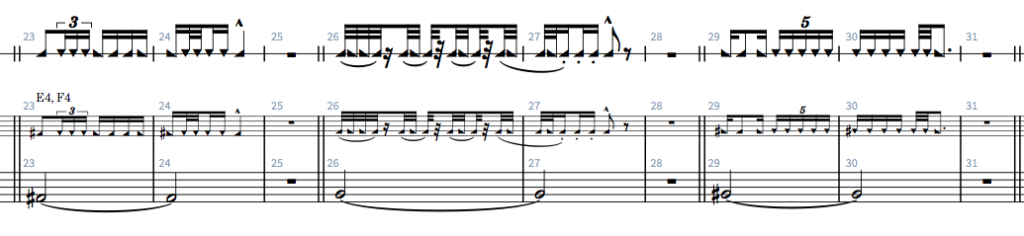

Each set of 37 variations on a sample is accessed from a range of 3 octaves plus one semitone. In the example below are my transcriptions for the three variations represented by the notes F#4, G4, and G#4. The duration of each note represents how long the scratch sample lasts. I made two attempts at a graphical representation of the actual scratching: one in an ossia staff above the notated staff, and one in a staff for untuned percussion. I’ll probably settle on the latter for clarity since there is no actual pitch, though the former is more elegant in its tighter visual grouping with the main staff.

Rhythm is the easiest characteristic to transcribe (though most require slowing the sample down to 1/2 speed to hear the specifics) and why standard notation lends itself so well to this task. To get the forward-backward scratching and a few other characteristics I use different noteheads and annotations.

- Triangle sloping up/down – forwards and backwards, respectively

- Triangle pointing down – any variation of the “chirp scratch” as defined at Timothy Wisdom’s website listed above

- Stacatto to denote a quick cutoff, can also be used with a chirp to denote an extremely short pop

- A tenuto (horizontal line above, not shown) to denote an unbroken movement

- A slur for a group of scratches played with no cutoff between them (though this can be ambiguous when the meter calls for a tie across two notes)

- A vertical wedge to denote the full sample sound (here “Aahh”), usually comes at the end of a sample

As you can imagine it’s an effort to transcribe each sample, but it provides an immediate reference library I can use in order to access each sample as needed when composing. Because of the difficulty and, more aesthetically, because any work benefits from an economy of material, I will likely only use one set of the “Fresh” and “Classic Aahh” when I start writing.