Once I’d heard about it, I looked far and wide for Ferneyhough’s book of essays and composer interviews but could only find it for $1,300+ used on Amazon (ik,r?) and listed elsewhere as out of stock. Some sites had PDFs but they were generally pay-to-view (Scribd is the main culprit, per usual). Several pages in to the Google results I found a very sketchy-looking site that had it for download. Cool with me. Pages are scanned with greater-or-lesser quality, some clean, some absurdly skewed as they were pressed against the copy machine but still readable. Later, I found a scan a bit cleaner but from an equally sketchy site. Also cool with me.

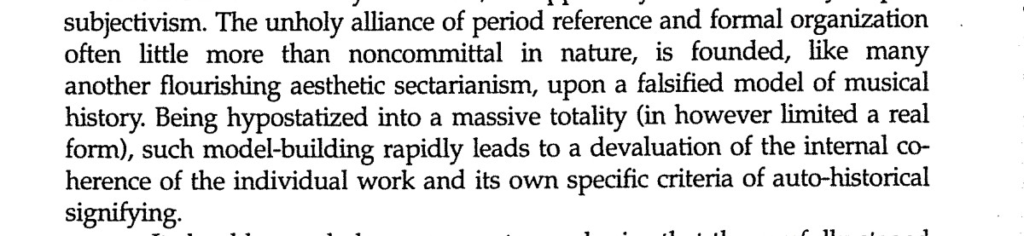

In one of his essays–I can’t find it now since, ugh, no CTRL+F [updated: found it, image below]–he makes a passing reference about the dead-end that is the choice of placing modern compositions into historic structures. Though he has written various string quartets and concertos, I understood him to mean classical forms internal to the work. In approaching the structure for Suite for Turntables and Piano, I had foolishly considered mimicking, with modern tonality, Bach’s suites (prelude, allemande, courante, etc.) and hint at each movement’s dance rhythms. I liked the idea of linking the history of turntablism to an historical form composed of various dances. I should have learned, though, from my initial but wisely abandoned intent to make the Interlude of my symphony a sort of postmodern Baroque piece. Such an approach is deeply flawed.

The unholy alliance of period reference and formal organization often little more than noncommittal in nature, is founded, like many another flourishing aesthetic sectarianism, upon a falsified model of musical history. Being hypostatized into massive totality (in however limited a real form), such model-building rapdily leads to a devaluation of the internal coherence of the individual work and its own specific criteria of auto-historical signifying.

Brian Ferneyhough. “Form – Figure – Style: An Intermediate Assessment (1982)” Collected Writings, page 22

(I upgraded from Dorico from 3 to 3.5 with good cause. This software continues to amaze and frustrate me, but mostly amaze. And most any time I’ve railed against it it’s been for bad cause. Original purchase was around $400 and the upgrade was $70. As an advocate of open source (both philosophically and economically) I balked but should not when skilled developers want to make well-earned money.)

I never wanted to write again for piano because, maybe for odd reasoning, I can’t play nearly at the level I could but maybe also because piano makes me write as a “rock” composer. I remember my piano teacher talking about how Poulenc’s vocal compositions were better than his piano ones because he wrote more musically and less pianistically. To write pianistically for piano sounds intuitively good, but I understand the flaws. I know that sometimes I wrote for piano what felt good in my hands but didn’t necessarily sound good.

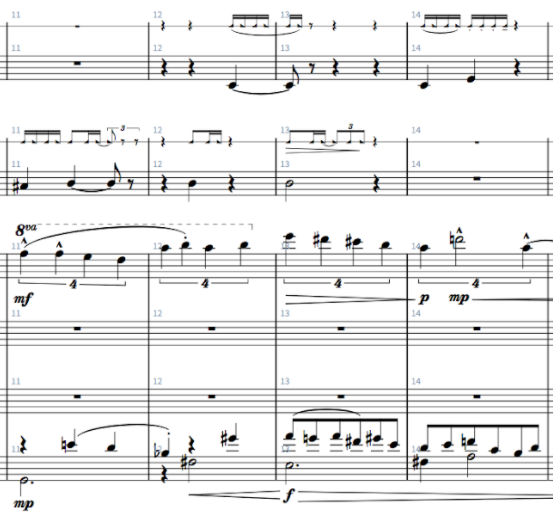

My time transcribing the UVI Scratch Machine samples was invaluable while composing. Though my transcriptions are only loose sketches of what the turntable sounds actually contain, they provide a helpful index of rhythms and “punctuation” of the scratches contained.

Below is an example of both the usefulness of the transcriptions and one of the egregious flaws of Dorico: unique dynamics for each piano staff are not obeyed during playback. My solution is to create two piano parts and dedicate one for treble and one for bass. Hacky but necessary.

As an instrument, I’m finding the turntable at times cold and yet at the same time rich with possibilities. It may just be the transition from writing for strings. This unfortunately might be a short piece just out of caution, even though I know from Prokofiev’s Concerto that the turntable lends itself to longer forms. That’s a shortcoming I need to overcome.