It’s an almost mundane trope now that DALL-E will obviate the need for visual artists and illustrators.

The most relevant counter to this is to look back at the advent of photography and its positive affect on artists, acting as a force compelling countless new approaches to visual expression. The effortless realism of photography changed the game–even if it was, at the beginning, crude realism. Artists came up with responses such as “vision”-base styles (Impressionism, Pointillism), psychologically-influenced styles (Symbolism, Expressionism, Fauvism), and then progressively further away from realism throughout the 1900s. Realistic and photorealistic works were still being created (Chuck Close’s work, certain periods of Gerhard Richter), but realism was now a choice. Influenced by the level playing field that photography provided, most anyone could afford their own portrait.

Driven by or co-incident with photography, “manual” visual artists also moved to more pedestrian subjects. Subjects such as boxing matches, picnics, and street scenes were added to the more rarified choices of portraits of the wealthy, scenes from mythology or religion, and the royal exploits such as hunting and whatnot. There were similar influences of subject matter prior to photography, but making realism almost effortless accelerated the direction of creativity in these areas. Rather than destroying the visual arts, photography prompted a Cambrian explosion of creativity.

The two YouTube videos below are from Vox. The first examines the history of and technology behind DALL-E and the second contains snippets of interviews with artists, art students, art professors, historians, and linguists discussing their thoughts, understandably evolving, on text-to-image generally and DALL-E specifically.

One argument made in the Vox interviews is that creativity will move from the execution of a physical work to the creation of more inventive prompts that will make DALL-E generate art of greater interest. With such a dynamic, creativity stops at the idea and no longer needs follow-through with physical skill and visual choices of media, style, palette, size, etc. Currently with DALL-E, most people appear interested in creating wacky scenes, though this is maybe similar to early photographs of simple, artless images created with a desire to marvel at the ease and near magical results. Also, think of the simplicity of early movies whose subject were rarely more complex that people walking down the street. The artist-as-prompter turns visual artists into writers.

I recently encountered my first prompted art used as illustration in an article (first image below, from the Galaxy Brain newsletter from Charlie Warzel). That use started a shit-storm directed at Warzel from conventional artists. Conversely, I also encountered my first de-commission of DALL-E art and instead a human artist being brought in (tweet below). In a subsequent tweet, the artist responds to a question as to why DALL-E lost the commission: “Impression I got was they were excited to use a new tool that ultimately couldn’t handle instructions/details on the level the job required.” Ultimately, this move to artist-as-prompters seems to me a dead-end to expressive art but not necessarily to illustration.

Even the indeterminacy used by Pollock, some of the Color Field painters, Fluxus, and others involve choice of media and technique, and with performance art styles such as Fluxus these choices are even removed from the artist (who defines a general structure to be adhered to) and left to the “audience”. Could the indeterminacy of DALL-E then be considered the medium that prompters use to create art?

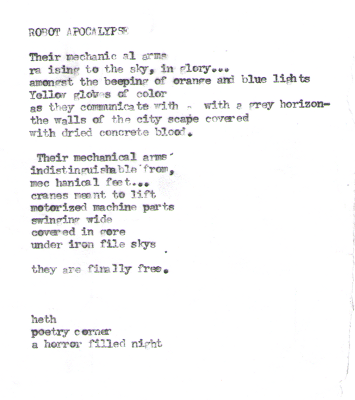

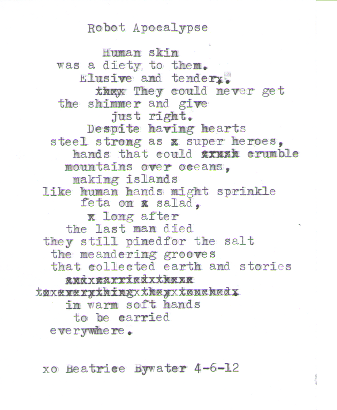

DALL-E might be more like collage, where the arrangement of the components are neither the choice of the artist/prompter nor of indeterminacy but rather the choice of DALL-E. Prompts consist of a palette of “clippings” that include objects, actions, emotions, and styles that already exist, and it is up to DALL-E to decide how to combine them. In this way, the prompter is commissioning DALL-E. I once prompted two street poets to each write a poem using the prompt “robot apocalypse.” I don’t take credit for the results.

(An aside: The music software Band-in-a-Box will auto-generate a song based on user-provided parameters including chord progression and style. The results are competently bland though, full disclosure, I have only listened to examples and have not used the software myself. The aural interest of the music it produces is far less than the visual interest of DALL-E’s creations so it’s an imperfect comparison, and iirc it was received with little trepidation by musicians. The people who would use the software would not have otherwise hired session musicians.)

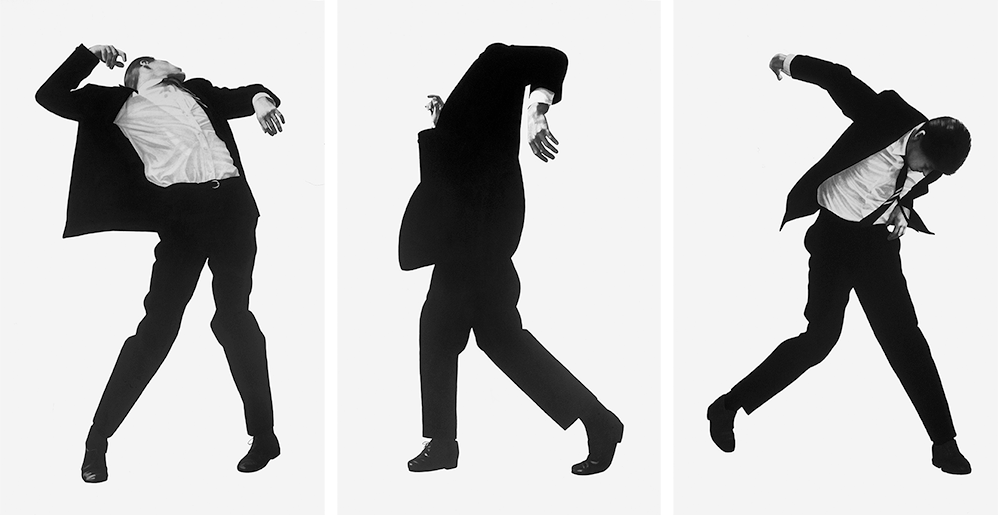

The first set of images below were generated by a co-worker using the prompt “man falls out of chair, wearing just a shirt, with his legs flying up in the air, while using the computer” (re-creating what happened to another co-worker). The second set is a work by the Artist Robert Longo, dated 1980-2000.

This accidental re-creation of an artist’s works decades prior brings up the derivative nature of DALL-E art and the potential for any depth of analysis in the result. Were DALL-E’s influences Robert Longo’s works? If so, unlike the borrowings that artists regularly make, DALL-E’s is taken out of context. And I may be being unfair in the comparison since the DALL-E prompt was intended humorously (and the image that generated three legs adds to the humor), but there is nothing other than surface to DALL-E’s creation while Longo’s work is the result of choices, unknown to the viewer, that exercise our analytical curiosity and therefore enhance our aesthetic enjoyment. Are the poses dancing or painful contortions? Is the white background an existential void or simply intended to force our focus on the man? Why a man and not a woman? Why a suit and not work clothes?

Which brings us to the concept of intentionality.

There’s a book by Steven W. Horst titled Symbols, Computation, and Intentionality. It’s a dense book–obviously–and though it’s been years and I’m pretty sure I never finished it (sigh), but one concept that has remained with me since my likely-partial-reading is that a barrier to artificial consciousness (more generally, negating a computational theory of mind) is “intentionality”. Put simply, from the opening of chapter three “Derived Intentionality”:

I shall argue that there are several distinct lines of argument to be had here [against CTM], but they share in common an intuition that there is something, either about the notion of symbolic representation in general or about representation in computers in particular, that makes it impossible to account for the semantic properties of mental states in representational terms.

I think of the definition of intentionality used here, in shorthand, as the directedness of conscious thought (though within this subject I’m on shaky intellectual ground). Looking at a work of art, we see an intentional act of the artist and it is those intentions that set off our emotional or intellectual curiosity.

There are two senses of “intention” here that may be unnecessarily confusing the issue: “intentionality” as the manifestation of concepts in the mind, and “artistic intention” as the desires of the artist. I see the first as the origin of the second and so, taking a long leap, see an emptiness in DALL-E’s flailing man on a chair when compared with Longo’s contorted man. Maybe the right prompt, the intentionality of the writer, would have created a more stylistically unique image.

Updated 31 Aug 2024

Regarding intentionality, from the article Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art by Ted Chiang (author of the short story that became the movie Arrival) in The New Yorker (emphases mine):

But a large language model is not a writer; it’s not even a user of language. Language is, by definition, a system of communication, and it requires an intention to communicate. Your phone’s auto-complete may offer good suggestions or bad ones, but in neither case is it trying to say anything to you or the person you’re texting.

And:

It is very easy to get ChatGPT to emit a series of words such as “I am happy to see you.” There are many things we don’t understand about how large language models work, but one thing we can be sure of is that ChatGPT is not happy to see you. A dog can communicate that it is happy to see you, and so can a prelinguistic child, even though both lack the capability to use words. ChatGPT feels nothing and desires nothing, and this lack of intention is why ChatGPT is not actually using language. What makes the words “I’m happy to see you” a linguistic utterance is not that the sequence of text tokens that it is made up of are well formed; what makes it a linguistic utterance is the intention to communicate something.