I became interested in the genre of New Complexity in modern music, then became familiar with the Major Names of that genre in both composition and performance along with those I appreciated the most, then–this being the world that it is–found that some of those Major Names are online, then I “kept informed” on social media of those that are active on social media. (Side note: I often contemplate with the gravity of history the fact that as a boy of five or nine I could have met Stravinsky or Shostakovich, respectively, despite my oblivious and underserving status at the time and their importance to me today.)

Ian Pace is a pianist and composer (see A week of “The History of Photography in Sound”) who is one of the above artists who are active online and who has at several times referenced the artist and composer Jim Aitchison. Mr. Pace had commissioned several works from Aitchison and posted photos and, though I can’t find those posts right now, they resonated strongly.

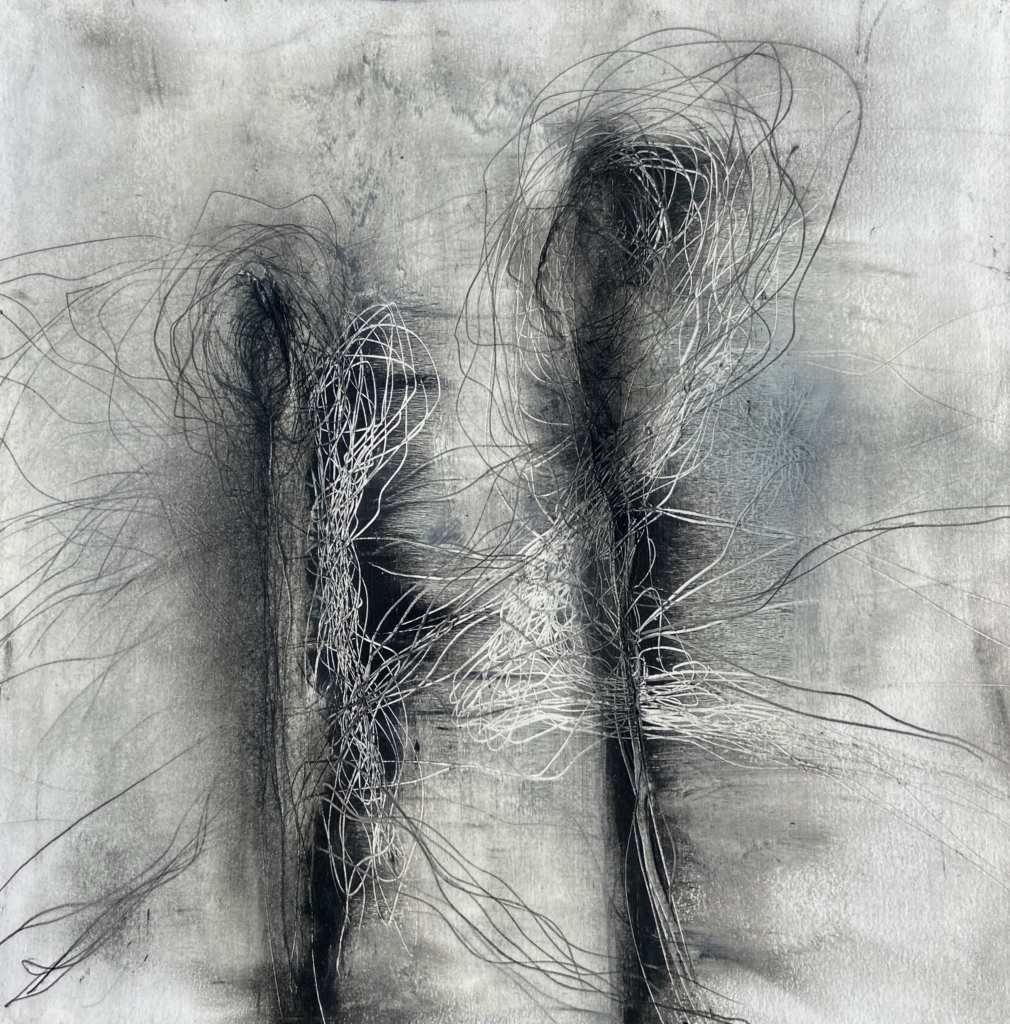

(I’m using the images from his web site because, although I received them a week ago, I have not yet had them framed or taken a quality photo.)

For some reason, I have sought out abstractions (rather, I have sought out what my drawing teacher labeled more precisely as “non-objective” works, because “abstract” denotes a physical thing that is being abstracted) to add to my collection over the past few years and I’ve seen works that I like? but that didn’t quite hit the emotion I was looking for. Ten years ago (to the month I see as I look back just now writing this) I purchased my first non-objective work–below–from a local Atlanta artist named Chris Strawbridge. It has always been a key work that, despite its apparent simplicity, I have enjoyed being a constant presence on our walls. Maybe that’s the reason.

I’ve purchased two beautiful works since then (by Wyatt Graff and Suzan Woodruff), but the first has had a longer time to burn into my psyche.

There’s a technical kinship between Aitchison’s Architecture of Landscape and Strawbridge’s Yoru that is belied by their emotional contrasts. Both use scumbling: Aitchison to help unify an active canvas, Strawbridge to provide a depth in the upper half to contrast the flatness of the bottom; and sgraffito: Aitchison, a little less visible in the image above but in reality he has absolutely brutalized the paper, to add both visual and tactile texture, Strawbridge to unify creatively discontinuous lines that cross the horizontal border in the center, the lower-half “chalk” lines are actually scraped to reveal a white base.

(Note that, apropos of everything, I used Strawbridge’s work as the one to represent my first symphony and Correspondence Fields (below) will be perfect for the orchestral suite that I’m working on based on the novel Figures in a Landscape.)

I felt a little weird about ordering all three (as if I were a flippant caricature of Zoidberg’s “one art, please” meme) but while I was immediately captivated by the Architecture of Landscape piece, I saw that he has worked with other approaches that were as interesting as they were in contrast to it. Correspondence Fields with its monochrome palette is a study in taught dualism between the sharp linear and soft tonal transitions that fight for the same space, white and black lines that attempt psychologically to tie the vertical figures together but that exist in separate space, and more obviously between the two figures themselves that are connected in type and via those extra-dimensional lines but that retain an aloof separateness. And Enigma Form I below is yet different than the first two with both a joyousness in its vibrant hues, made more intense by the heavy black, and a vibrating calm/terror of its outer space void.