A month or so ago a picture from one of the Barbarella comic books came across my feed and it was graphic design catnip. There was an unexpected clarity from something I would have expected to be garish at best. I’ve learned that there is a legacy that she has left that is more respectful and appreciative than I would have thought. I mean, how can I be blamed…

But the clean, stylish image that was posted inspired me to take a look at the original comic and watch the movie that I had started years ago but was put off by because of the silliness. I think it was the early scene where two young girls kidnap Barbarella and they sledded across a frozen landscape pulled by the special effects apotheosis of 1968 in the form of a rubber manta ray with a few extra carbuncles glued on, all while groovy Tom Jones-type music played. It was uncomfortably daft, and at the time I just gave up and labeled the movie as a thing-that-you-hear-about-but-never-watch.

The movie is available to rent from various streaming services but PlutoTV offers it for free and uncut and it’s also on The Internet Archive if you want it sans commercials. It was enjoyable and intentionally silly at times–though the intentional silliness I suspect doesn’t always align with the actual–and a friend said they had the same reaction when they rewatched it years ago: not so unwatchable as they’d remembered. The movie feels very much like a stylistic precursor to The Fifth Element but maybe it’s just the French lineage of both (Luc Besson having ripped off the French graphic novel The Incal). Having watched the movie I decided to then have a go at the source material.

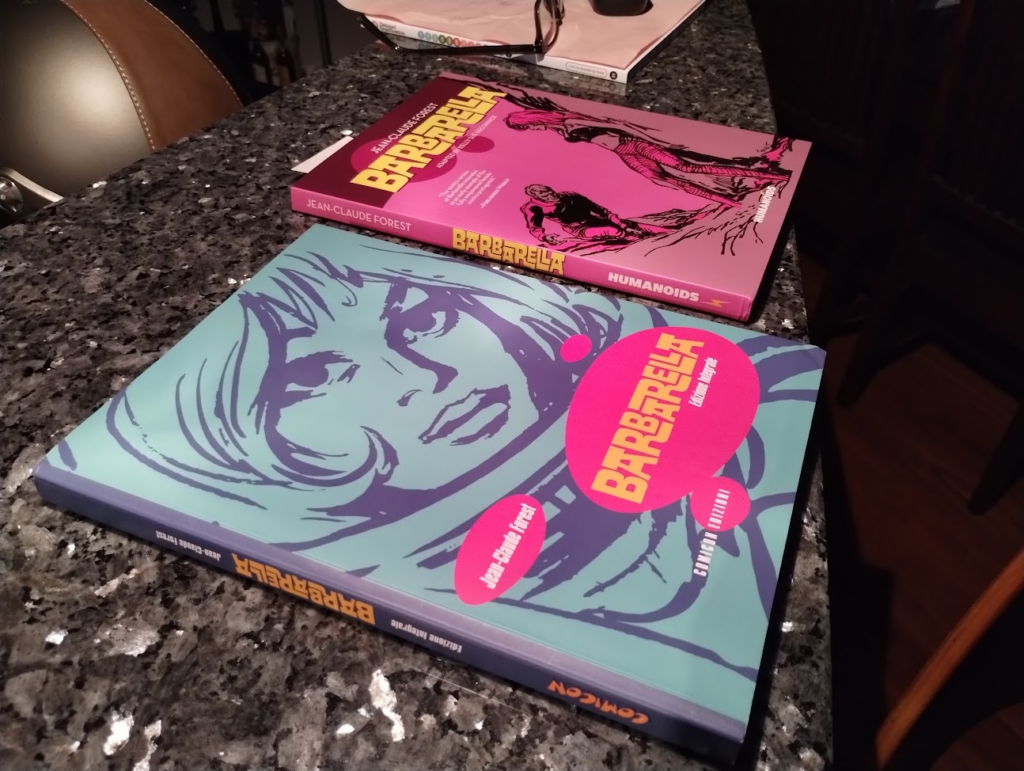

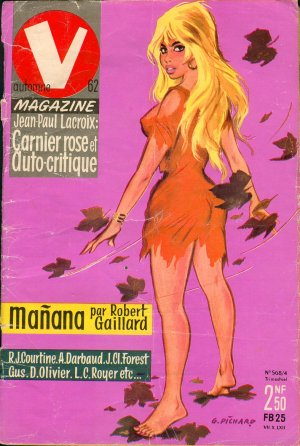

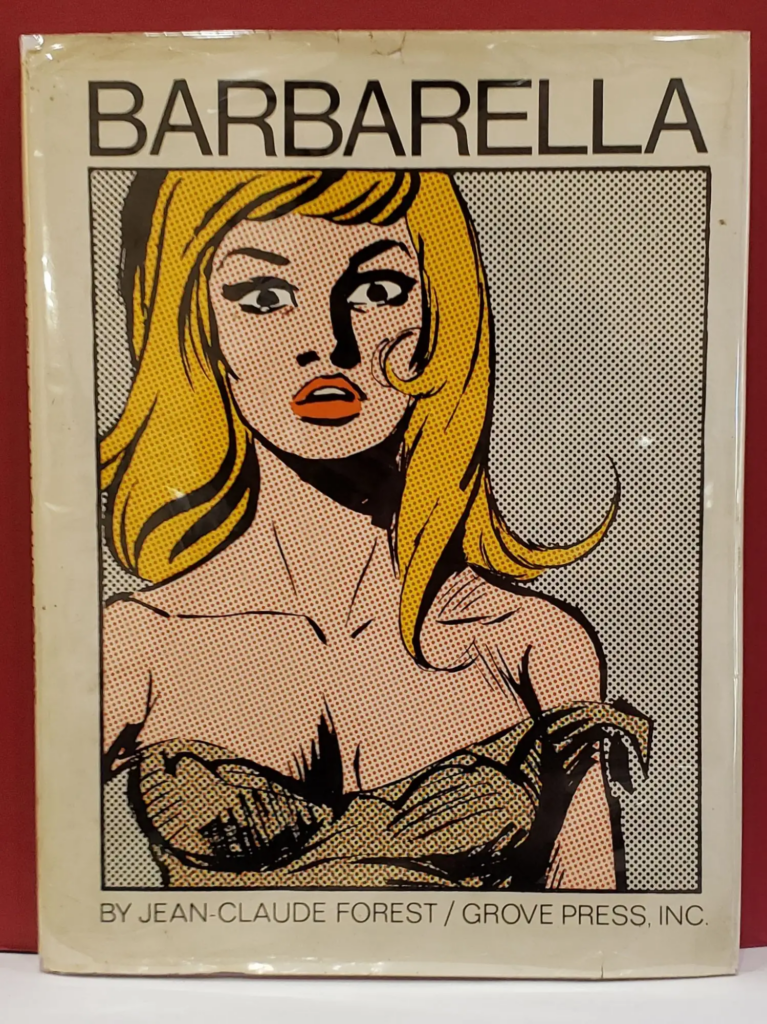

In 2014, the publisher Humanoids released a new English-language translation of the first two graphic novels, Barbarella and Les Colères du Mange-Minutes (The Rage of the Minute-Eaters) in a single volume. The Italian-language edition of the same also came out in 2016 but under a different publisher, with near-identical design, however I’m not aware of any actual connection. The English-language translation is written by the comic book author (and feminist champion) Kelly Sue DeConnick. The original comic was serialized in V-Magazine in 1962, the movie in 1968. Both have “adult” scenes but are not at all exploitative despite christening Jane Fonda’s “sex kitten” career phase so the re-owning by a feminist artist is an important analytical jumping-off point.

With regard to social relevance at the time of publication, Paul Gravett has an excellent article (some of it used as an introduction to the 2014 edition) on Barbarella’s origins and her place in the social history of the preceding decades. Highly recommended:

To put Barbarella’s heyday into some context we need to time-travel back to the aftermath of the Second World War. Moral panics soon broke out in many countries, prompted by fears about the future, embodied in children and childhood in general, and about rising juvenile delinquency, hardly surprising considering the societal and familial damage caused by the conflict. Rather than deal directly with the more complex roots of this problem, politicians and various interest groups sought causes and scapegoats elsewhere in the mass media, and in particular in the least defensible medium presumed to be solely for children – comics.

This would sound quaint if we weren’t in the society we are today and one that is arguably more reactionary.

The “satanic panic” over comics in post-war Europe is of the same category with the creation of sukeban gangs in post-war Japan and the themes in The Who’s Quadrophenia. All three situations were the result of disaffected youth (is there any other type?) from fractured families combined with a strengthening middle class that gave them money and free time but no faith that society has a place for them. In Japan, the culture’s sexism and sudden import of American pop culture helped created the independent girl gangs; in the UK, Mods did not want to live like their working-class parents and so rebelled with fashion and, later, with drug use. All three have their roots in World War 2.

Considering Barbarella in her graphic novel origins, the images presented in compilations have that Lichtenstein aura (his comics-reproduction period beginning at the same time) that his mirrors-reflecting-mirrors art created/was created by. Post-Lichtenstein it’s hard not to see certain panels with a sculptural permanence.

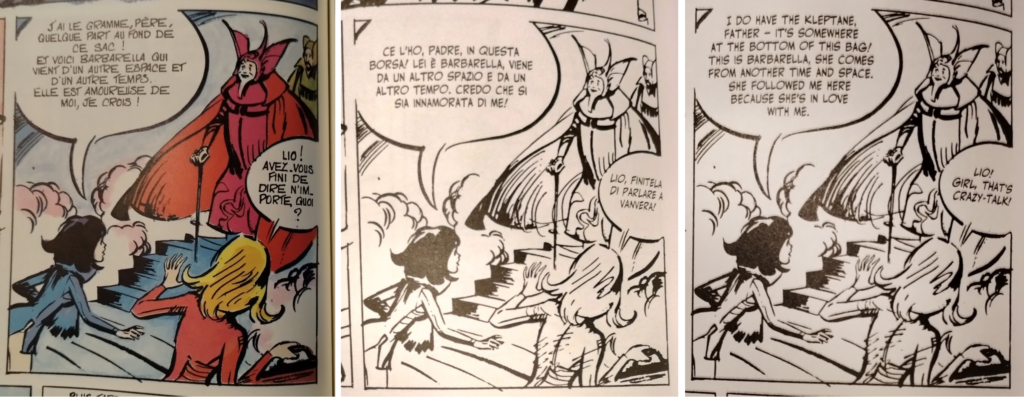

After reading some commentary on the nuance of the DeConnick translation I became obsessed with one particularly charming panel of hers for The Rage of the Minute-Eaters and I wanted to see how it differed from the source material. I currently have the 1985 Dargaud release (page 20) along with the Italian (page 92) and English (page 94) versions from 2016.

Ignoring the differences that were made in the art in the earlier French version (note Barbarella’s hair and Lio’s father’s cape), the translation choices are fun. Looking at just the statement by Lio preceding Barbarella’s reply and her reply (I kept the comic script ALLCAPS to avoid any grammatical questions). Lio:

- ELLE EST AMOUREUSE DE MOI, JE CROIS!

- CREDO CHE SI SIA INNAMORATA DI ME!

- SHE FOLLOWED ME HERE BECAUSE SHE’S IN LOVE WITH ME.

And Barbarella:

- LIO! AVEZ_VOUS FINI DE DIRE N’IM_PORTE, QUOI?

- LIO, FINITELA DI PARLARE A VANVERA!

- LIO! GIRL, THAT’S CRAZY-TALK!

OK, let’s stop and just admit that Barbarella’s response is Absolutely Awesome in the English translation. The Italian I can comfortably-ish translate to “Lio, stop that reckless talk!” They’re similar but DeConnick has a more sassy twist to it.

[ Updated 5 Nov 2023: and here’s the panel from the German version Die Neuen Abenteuer der Barbarella, page 16:

LIO! IST DAS ALLES, WAS DIR DAZO EINFAELLT!

Loosely: “Lio! Is that all that you can think of!” ]

Regarding the art changes, Gravett makes note:

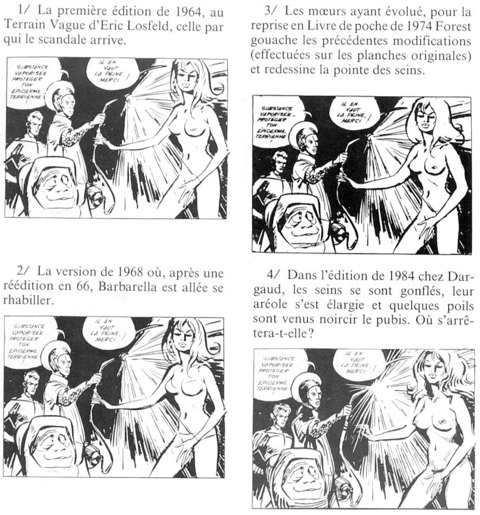

The French ban on Barbarella was never lifted and for subsequent re-editions Forest would revise his artwork, making it more, or less, tame to suit the times.

And provides examples of changes between the original 1964 art, the 1966 American release, the 1974 Le Livre De Poche release, and the 1984 Dargaud release (the publication that made these comparisons is not mentioned). From the editions I currently have, the panel in question is on page 20 (2014 English edition), page 22 (2016 Italian edition), and page 35 (1988 J’ai Lu edition):

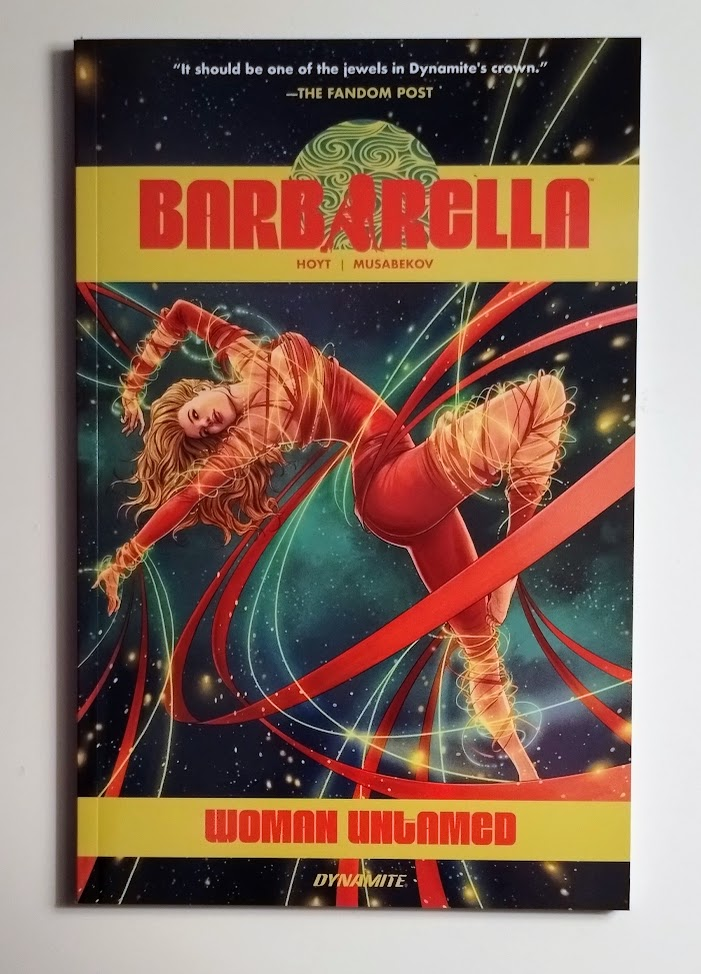

A new series was published by Dynamite starting in 2017 with a 12-issue arc and in 2021 with a 10-issue arc. The 2017 story arc is glossy and has some very nice artwork by Kenan Yarar and some genuinely funny moments. The first volume of the 2021 story-arc is… less entertaining. Possibly the bland art is at fault. The collected volumes are below but Dynamite is absolutely shameless in their single-issue variant covers with probably 3 or 4 for each single issue. Overall average.